Handwritten digits recognition from scratch in Rust - Part 1: The Neural Network

Welcome back to this series about digits recognition! Today, we’ll directly dive in the center of our topic, by implementing the neural network.

After a quick recap about what we want to achieve, we will initialise our Cargo project and start coding a struct representing our neural network.

The parts of our Neural Network

The input

As you will see in Part 2, the images we’ll be working with have a 28px side. So, to be able to recognise the digits, we will need a kind of “machine” that takes 28px images as an input. In our case, we don’t care much about color, so we’ll work with grayscale images. This means that each pixel have a value somewhere between 0 and 1, 0 being the darkest black and 1 being the lighest white. Hence, the machine we need to build takes as an input 28*28 = 784 floating numbers between 0 and 1.

![]() Our image as an input. (Credit: 3Blue1Brown)

Our image as an input. (Credit: 3Blue1Brown)

Code-wise, our neural network will then take as an input a Vec<f64>, of size 784.

Note: For this tutorial, I decided to use Vectors to represent many structures. There’s multiple alternatives, like using arrays, or even vectors and matrices from the nalgebra crate (more on that later). For the sake of simplicity, we’ll stick with Vectors and not arrays, since they can be dynamically allocated.

The output

To be fair, there’s multiple ways to represent the output of our machine. We want it to return an integer between 0 and 9, but neural networks, as we’ll see, don’t work much with integers, but instead with floating numbers.

So how can our neural network tell us which digit it detected? By using 10 outputs, one corresponding to each digit. We will then check which output is the most “activated”, and deduce the corresponding digit. In fancy terms, we will take the argmax of the output layer.

The intermediate layers

The choice of the number and sizes of intermediate layers is kind of… random? As long as the intermediate layers are not too small nor too large, we should be good. And one great thing about coding, is that you can adjust things up at the end.

Hence, I chose two intermediate layers, of 16 neurons each (kind of a reference to 3Blue1Brown’s video), but out implementation of the neural network will take these as an argument, making it super-convenient to change later on.

To do so, we’ll store the size of each layer inside a Vec<usize>. If the intermediate layers can be changed by the “user”, we’ll have to make sure that the first element of the Vec is a layer of 784 input neurons, and that the last one is a layer of 10 output neurons.

But how does a neural network propagate activation?

I won’t go into details of propagation, since it is perfectly explained by 3Blue1Brown, but here’s a summary. For the activation to propagate between layers, a neural network uses weights, for each connection between two neurons of two layers, and biases, one per neuron of the second layer.

Mathematicaly, if we consider the propagation between the layer $i$ and $i+1$, and that we index the activations of the layer $i$ from $1$ to $n$, we have for every activation $a_m^{(i+1)}$ of the layer $i+1$:

\[a_m^{(i+1)} = \sigma(w_{m, 0} a_0^{(i)} + w_{m, 1} a_1^{(i)} + ... + w_{m, n} a_n^{(i)} + b_m)\]Where $\sigma$ is the activation function, and $w_{m, k}$ is weight connecting the $k$-th neuron of layer $i$ to the $m$-th neuron of the layer $i+1$, and $b_m$ the bias of the neuron $m$.

But this is a lot of notations, and indices… Hopefully, this can be written more in a more concise way, using matrices:

\[a^{(i+1)} = \sigma(W^{(i)} \times a^{(i)} + B^{(i)})\]Where $W^{(i)}$ is the weights matrix, and $B^{(i)}$ is the biases vector.

If you’re a bit lost here, do not worry. You only need to understand that we can represents weights as matrices, and biases as vectors.

Weights and biases

That being said, we will represent the weights as matrices, and biases as vectors (in the linear algebra way). To keep things consistent, we will have a Vec-only approach of representing our weights and biases. This means that the weights between two layers will be a Vec<Vec<f64>>, and that the biases will be a Vec<f64>.

Note: Hand-coding the linear algebra part is, in my opinion, the best way to keep it simple. Nevertheless, if you’re feeling confident and not afraid to adapt some code I’ll write, using nalgebra, a linear algebra library, will be much more efficient, and you won’t have to write some boring matrix multiplication functions.

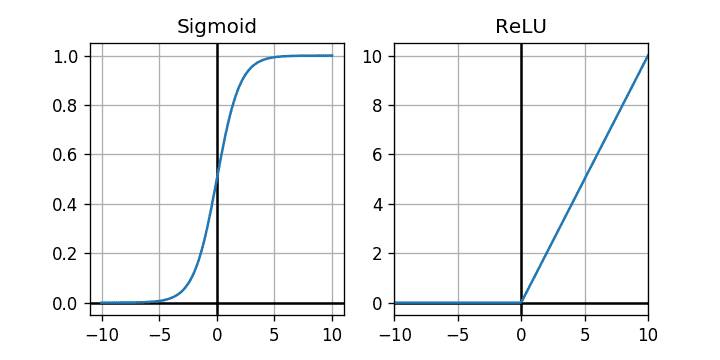

The activation function

To make things a bit more general, our neural network object will take the activation function as an argument. We will only implement two different ones, Sigmoid and ReLU, but we’ll make sure that adding a new one is quite simple.

The graphs of Sigmoid and ReLU.

The graphs of Sigmoid and ReLU.

Let’s code!

Enough tchit-tchat, let’s get to the fun part, shall we?

Project initialisation

We’ll use Cargo to simplify the setup of our project. Enter in your terminal:

$ cargo new digits_recognition

Cargo will then create for you a new folder containing default files:

digits_recognition

├── src

│ └── main.rs

├── Cargo.toml

└── .gitignore

If you enter this new folder, you can make sure that eveything is working by running the project:

$ cd digits_recognition

$ cargo run

Compiling digits_recognition v0.1.0 (.../digits_recognition)

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.99s

Running `target/debug/digits_recognition`

Hello, world!

So far, so good.

The NeuralNetwork struct

Let’s keep things clean and avoid coding directly in the main.rs file, that we will use later as a launcher. Let’s create a new neural_network.rs file in the src folder, and add a simple struct called… NeuralNetwork.

/// A structure containing the actual neural network layers, weights, and biases.

struct NeuralNetwork;

In the main.rs file, also add on top:

mod neural_network;

This is not absolutely mandatory right now, but if you’re using rust-analyser - and you should, it will take into account the new file.

What does our neural network need? A way to store the layers sizes, plus weights, biases, and an activation function:

/// A structure containing the actual neural network layers, weights, and biases.

pub struct NeuralNetwork {

/// The number of neurons in each layer, including first and last layers.

layers: Vec<usize>,

/// The weight of each synapse.

weights: Vec< Vec<Vec<f64>> >,

/// The bias of each synapse.

biases: Vec< Vec<f64> >,

/// The activation function and its derivative.

activation_function: ...

}

Note: I use /// to add documentation comments, that will be nicely displayed when hovering identifiers, with tools like rust-analyser.

We already discussed the representation of one weight matrix, and one bias vector. Here, we contain them in a new Vec: weights is a Vector of matrices. Same goes for biases, a Vector of vectors.

We simply need to find a way to represent our activation function. We could store directly a function with type f64 -> f64, but there’s two issues with this. First, it’s not easy in Rust: the type dyn Fn(f64) -> f64 cannot easily be stored, and passing it as an argument everytime we need to use it is quite ugly. Second, we do not only need the activation function, but also its derivative. Hence, it would be clean to be able to “group up” a function and its derivative.

The simplest way I found is to create a dedicated struct for our activation function. For now, let’s just create a new struct:

pub struct ActivationFunction;

And specify that we want the activation_function field from NeuralNetwork to be of type ActivationFunction:

pub struct NeuralNetwork {

...

/// The activation function and its derivative.

activation_function: ActivationFunction

}

We will handle the methods from ActivationFunction when we will need them.

Network initialisation

Now that we have our struct outline, we will need a way to create a new, random neural network. Let’s call this function random. Since our weights and biases will be random, we only take layers and activation_function as arguments:

impl NeuralNetwork {

/// Initialise a new Neural Network with random weights and biases.

pub fn random(

layers: Vec<usize>,

activation_function: ActivationFunction

) -> Self {

Self {

layers,

weights: todo!(),

biases: todo!(),

activation_function

}

}

}

Tip: The todo! macro comes very handy to write parts of your code later, while making sure that Rust and cargo check understands that’s there’s no bug. This avoids having your entire screen red because of errors when using the handy rust-analyser.

Random weights and biases

To build the Vectors containing the weights and biases, we’ll start with an empty vec![], and progressively add the generated matrices/vectors. The hard part is to keep in my the dimensions of the matrices we want: the weights connecting the layer number $i$ to the layer number $i+1$ needs to have layers[i+1] lines and layers[i] columns.

// Initially empty vectors

let mut weights = vec![];

let mut biases = vec![];

// Note the -1: the output layer is not connected to anything

for i in 0..layers.len()-1 {

let mut w_matrix = vec![];

let mut b_vector = vec![];

for _ in 0..layers[i+1] {

// Push a random bias in the biases vector

b_vector.push(todo!());

// TODO: generate a random number

// Push a random line of weights in the matrix

let mut line = vec![];

for _ in 0..layers[i] {

line.push(todo!());

// TODO: generate a random number

}

w_matrix.push(line);

}

weights.push(w_matrix);

biases.push(b_vector);

}

The only part now missing is the actual random numbers.

To generate random weights and biases, we will need a random numbers generator, provided by the rand crate. While we’re at it, let’s also add the rand-distr crate to our project; it will allow us to specify to probability distribution of our number generator. Basically, we want our random numbers to be distributed somewhere around 0.0.

To add the crates to your project, insert the following lines to your Cargo.toml file:

...

[dependencies]

rand = "0.8.4"

rand_distr = "0.4.2"

And include the crates in your project by adding, at the beginning of your neural_network.rs file:

use rand_distr::{Normal, Distribution};

The base code to generate a random number, using the normal distribution, will be:

// Normal distribution sampler

let normal = Normal::new(0.0, 1.0).unwrap();

// 0 is the mean, and 1 is the standard deviation

// Random number generator

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

// Generated number

let number = normal.sample(&mut rng);

Let’s add this to the code we previously written:

// Normal distribution sampler

let normal = Normal::new(0.0, 1.0).unwrap();

// Random number generator

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

...

for i in 0..layers.len()-1 {

...

for _ in 0..layers[i+1] {

// Push a random bias in the biases vector

b_vector.push(normal.sample(&mut rng));

...

for _ in 0..layers[i] {

// Push a random weight in the weights matrix line

line.push(normal.sample(&mut rng));

}

...

}

...

}

Putting it all together:

pub fn random(layers: Vec<usize>, activation_function: ActivationFunction) -> Self {

let normal = Normal::new(0.0, 1.0).unwrap();

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let mut weights = vec![];

let mut biases = vec![];

for i in 0..layers.len()-1 {

let mut w_matrix = vec![];

let mut b_vector = vec![];

for _ in 0..layers[i+1] {

b_vector.push(normal.sample(&mut rng));

let mut line = vec![];

for _ in 0..layers[i] {

line.push(normal.sample(&mut rng));

}

w_matrix.push(line);

}

weights.push(w_matrix);

biases.push(b_vector);

}

Self { layers, weights, biases, activation_function }

}

Feeding forward

Creating a new neural network is nice, but using it is even better. So, let’s implement a feed-forward function.

What we want to do, is tell the neural network “Hey, take this 784-long Vec<f64>, and give me a 10-long Vec<f64> back”:

/// Computes the activations of the output layer, given the activations of the input layer.

pub fn feed_forward(&self, mut activation: Vec<f64>) -> Vec<f64> {

todo!()

}

This process is called feed-forward, because the neural network will actually compute the activations layer by layer, going forward from the input layer towards the output layer. As a reminder, to move from one layer to the next one, the different steps are:

- Multiply the latest activation vector by the weights matrix

- Add the biases to it

- Apply each the activation function to each coefficient

Written in a fancy mathematical way, the activations of the layer number $i+1$, that we’ll call $a^{(i+1)}$ can be expressed depending on the activations of the activations of the precendent layer, $a^{(i)}$, with the following formula:

\[a^{(i+1)} = \sigma(W^{(i)} \times a^{(i)} + B^{(i)})\]Where $\sigma$ is the activation function, $W^{(i)}$ is the weights matrix, and $B^{(i)}$ is the biases vector.

Function outline

This translates pretty smoothly into code:

/// Computes the activations of the output layer, given the activations of the input layer.

pub fn feed_forward(&self, mut activation: Vec<f64>) -> Vec<f64> {

for i in 0..self.layers.len()-1 {

// Multiply the activation by the weights matrix

activation = self.weights[i] * activation;

// Add the biases

activation += self.biases[i];

// Apply the activation function to each coefficient

for i in 0..activation.len() {

activation[i] = self.activation_function.activation(activation[i]);

}

}

activation

}

oh waitt this is not Python, so we can’t just mutliply and add Vecs…

Well then, let’s get into…

Unoptimised linear algebra

Programming matrix multiplication and linear algebra in general is an entire topic, dare I say an art. But today, for the sake of simplicity, we’re not gonna do art.

We have to code two functions: one to multiply a matrix by a vector, and one to add a vector to another vector. Let’s create a new file called linear_algebra.rs, and add our two functions outlines:

/// Given a matrix `A` and a vector `X`, returns the vector `AX`.

pub fn matrix_vector_product(matrix: &Vec<Vec<f64>>, vector: &Vec<f64>) -> Vec<f64> {

assert_eq!(matrix[0].len(), vector.len(), "The matrix and vector shapes are incompatible.");

todo!()

}

/// Given one mutable vector `X1` and another vector `X2` of the same size, adds `X2` to `X1`.

pub fn vectors_sum(vector1: &mut Vec<f64>, vector2: &Vec<f64>) {

assert_eq!(vector1.len(), vector2.len(), "The two vectors have different sizes.");

todo!()

}

The simple part first: vectors_sum, which is close to trivial.

/// Given one mutable vector `X1` and another vector `X2` of the same size, adds `X2` to `X1`.

pub fn vectors_sum(vector1: &mut Vec<f64>, vector2: &Vec<f64>) {

assert_eq!(vector1.len(), vector2.len(), "The two vectors have different sizes.");

for i in 0..vector1.len() {

vector1[i] += vector2[i];

}

}

Even though, there’s a few things worth mentionning:

- Note that we use references (

&) as arguments. This allows Rust to avoid moving the vectors, which makes the code much more efficient. Without references, Rust would actually complain, because it knows that movingVecs is time-consuming. - Only the first reference is mutable (

mut). Makes sense, we do not want to modify the bias vector. - Our function does not return anything: the function will be called, the first vector will be modified, but nothing is returned. This is actually much more efficient than allocating new memory for the result of

vector1 + vector2, and using this new memory space as our base for future operations.

Now, let’s get to the though one. If you forgot how to multiply a matrix and a vector by hand, try to reactivate your memory before actually entering the coding part.

/// Given a matrix `A` and a vector `X`, returns the vector `AX`.

pub fn matrix_vector_product(matrix: &Vec<Vec<f64>>, vector: &Vec<f64>) -> Vec<f64> {

assert_eq!(matrix[0].len(), vector.len(), "The matrix and vector shapes are incompatible.");

// Initialise an empty vector

let mut result = Vec::with_capacity(matrix.len());

for j in 0..matrix.len() {

result.push(0.0); // add a null coefficient to the vector

for i in 0..vector.len() {

// add the result of the multiplication to the coefficient

result[j] += matrix[j][i] * vector[i]

}

}

result

}

Let’s see how my previous remarks translate to the new function:

- We also use references, for the same reasons.

- Our function does return a new

Vec. It’s not as efficient as our first function, but there is not simple way to avoid it. - Both references are unmutable. Since we’re not modifying anything, but starting fresh, we do not need to have mutable objects.

Activation function

We can’t procrastinate the coding of ActivationFunction any further. In feed_forward, we wrote:

activation[i] = self.activation_function.activation(activation[i]);

Therefore, we have to build the activation function, of ActivationFunction.

For now, all we have is an empty struct:

pub struct ActivationFunction;

What we will do, is instead of storing the activation function, we will only store its type. Then, when we’ll call activation_function.activation, we’ll return the adapted result depending on the stored type.

The type will be an enum:

pub enum ActivationFunctionType {

Sigmoid,

ReLU

}

pub struct ActivationFunction {

/// The activation function, which will dictate the main function and its derivative.

function_type: ActivationFunctionType

}

impl ActivationFunction {

/// Create a new ActivationFunction of given type.

pub fn new(function_type: ActivationFunctionType) -> Self {

ActivationFunction { function_type }

}

}

And the activation function looks like this:

/// The main activation function, depends on the type.

pub fn activation(&self, x: f64) -> f64 {

match self.function_type {

ActivationFunctionType::Sigmoid => sigmoid(x),

ActivationFunctionType::ReLU => ReLU(x)

}

}

/// Logistic function.

fn sigmoid(x: f64) -> f64 {

1.0 / (1.0 + (-x).exp())

}

/// Rectification function.

#[allow(non_snake_case)]

fn ReLU(x: f64) -> f64 {

f64::max(x, 0.0)

}

Note: Calling a function ReLU upsets Rust a little, since it does not respect the snake_case naming convention. As a general rule of thumb, one should always follow Rust’s conventions. But this time, just this time, we’ll make an exception, since this makes more sense than relu, which isn’t the common spelling. To tell Rust “don’t worry, I know what I’m doing”, we just have to disable the warning with the #[allow(non_snake_case)] line above the function’s name.

We now have all the parts to have a working feed_forward function! Let’s put it all together:

use crate::linear_algebra::*; // Includes the linear algebra functions from the other file

/// Computes the activations of the output layer, given the activations of the input layer.

pub fn feed_forward(&self, mut activation: Vec<f64>) -> Vec<f64> {

for i in 0..self.layers.len()-1 {

// Multiply the activation by the weights matrix

activation = matrix_vector_product(&self.weights[i], &activation);

// Add the biases

vectors_sum(&mut activation , &self.biases[i]);

// Apply the activation function to every coefficient

for i in 0..activation.len() {

activation[i] = self.activation_function.activation_function(activation[i]);

}

}

activation

}

Note: We can use a more idiomatic Rust syntax instead of the last for loop: activation = activation.iter().map(self.activation_function.activation).collect();. Iterators are a center part of Rust, but can be a bit tricky when coming from other programming languages. What we simply do here, is iterate over the elements of activation with .iter(), then map the activation function to each element using .map(...). Finally, we transform our modified iterator back to a Vec using .collect().

That was a lot of code for what looked like a simple function. But that’s the price to pay for not using slightly complex crates such as nalgebra. Even though, I find that understanding basic matrix multiplication is much needed when you’re using matrices. Now, don’t worry, we’re almost done with the neural network.

Prediction

To have a fully working, untrained digit recogniser, we just need to transform the activations of output layers into… a digit. Compared to what we just did, it will look like a piece of cake. Let’s code a predict function, that takes an “image” as an input (de facto, a 784-long Vec<f64>), and that returns a digit (stored as a u8 integer):

/// Predicts the digit in a given image.

pub fn predict(&self, input: Vec<f64>) -> u8 {

// Get the output layer's activations

let result = self.feed_forward(input);

// Select the highest activation of the output layer.

let mut maxi = (result[0], 0);

for i in 1..result.len() { // we start at 1, since values of index 0 is already set as the current maxi

if result[i] > maxi.0 {

maxi = (result[i], i);

}

}

maxi.1 as u8

}

Wrapping it up

Good job, Part 1 is done! Let’s summarize it all.

What we’ve done

We’ve coded a lot of important parts of our neural network:

- The random initialisation

- The

feed_forwardmechanism, with its linear algebra functions - A nice way to store different activation functions

- The

predictfunction

What we will do next time

In Part 2, we’ll actually use the neural network! We’ll start by loading some images, then we’ll predict which digit they contain with our random neural network. See you next time!